Introduction: More Than Just Four Walls

The concept of ‘home’ transcends mere physical structure; it embodies a profound and multifaceted idea deeply interwoven with our social, cultural, and personal identities. It’s a space where personal narratives unfold, traditions are nurtured, and a sense of belonging takes root. From the imposing fortresses of the medieval era to the sleek, technology-integrated smart homes of today, the meaning and function of ‘home’ have undergone a dramatic transformation, mirroring the evolution of society itself. This article embarks on a journey through time, exploring how societal shifts, technological advancements, and cultural changes have molded our understanding of this fundamental human concept, delving into its architectural, sociological, and deeply personal dimensions. The history of home reflects our changing relationship with the world around us, from prioritizing security and shelter to embracing self-expression and interconnectedness. Consider, for instance, the shift from the communal hearths of medieval longhouses, where family and community life intertwined, to the individualized spaces of modern apartments, reflecting the growing emphasis on personal privacy. This evolution in home design speaks volumes about the changing social fabric of our times. The very architecture of our homes tells a story, reflecting prevailing cultural values and technological possibilities. Medieval homes, often designed as fortified structures, emphasized security and hierarchy, while modern homes prioritize open-plan living and integration with the natural world, reflecting a shift towards community and well-being. Interior design trends further illuminate these shifts, with the ornate embellishments of Victorian homes giving way to the minimalist aesthetics of contemporary design, mirroring changing notions of comfort and status. From a sociological perspective, the concept of ‘home’ is intricately linked to family structures, social class, and community dynamics. The rise of suburbanization in the mid-20th century, for example, witnessed the emergence of the nuclear family ideal, reflected in the design of single-family homes with private yards. This shift also impacted community interactions, leading to both increased privacy and a potential sense of isolation. Cultural studies offer further insights into how ‘home’ is perceived and experienced across different cultures. In some cultures, ‘home’ is deeply connected to ancestral lands and traditions, while in others, it represents a more fluid and adaptable concept, reflecting the realities of global migration and displacement. Ultimately, the concept of ‘home’ is a dynamic and evolving one, shaped by a complex interplay of historical, social, technological, and cultural forces. This exploration of ‘home’ through the ages will reveal how this fundamental human need continues to be reinterpreted and redefined in response to the ever-changing world around us.

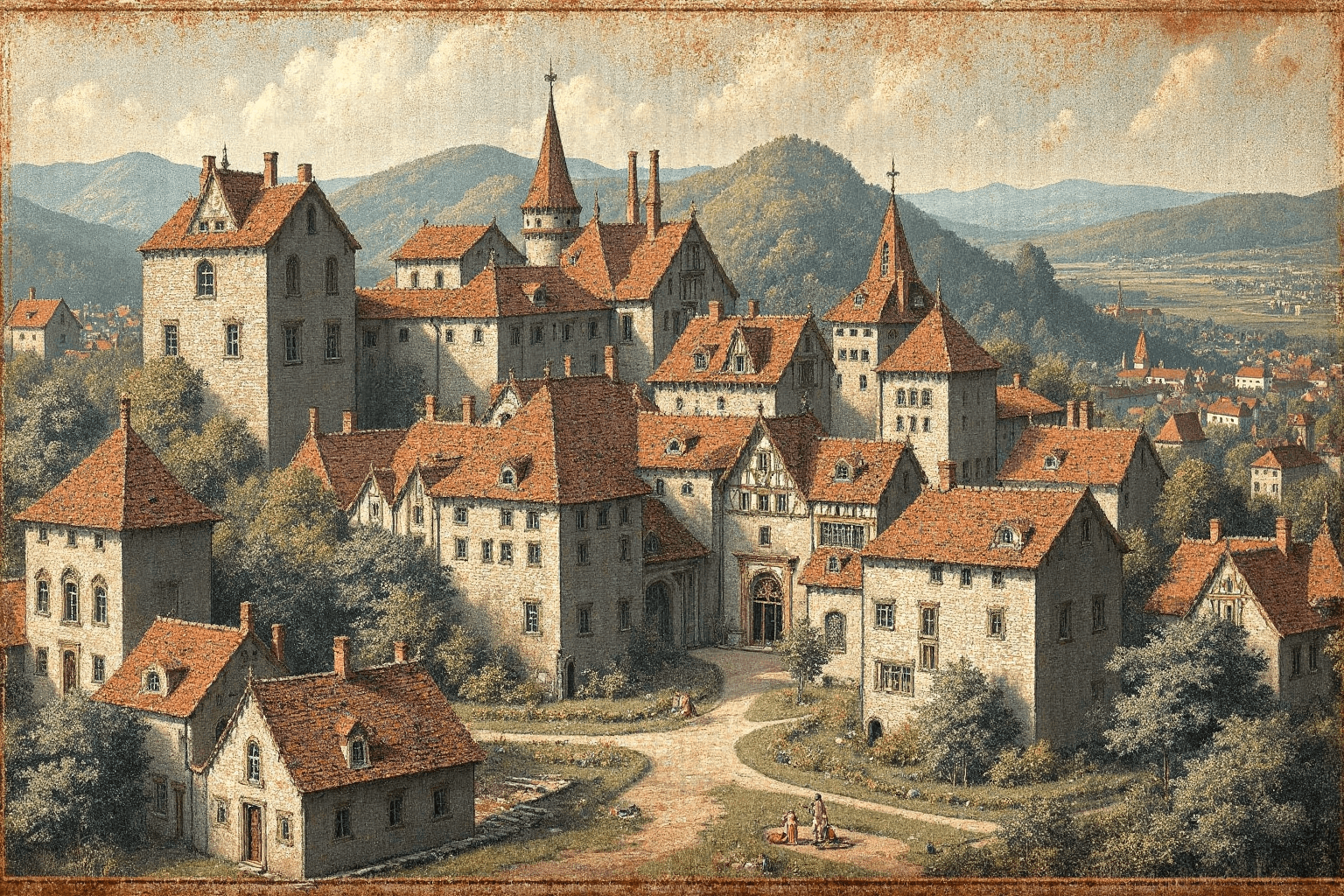

Medieval Homes: Fortresses and Family

In the medieval period, the concept of \”home\” was profoundly shaped by social hierarchy, the ever-present need for security, and deeply rooted religious beliefs. For the nobility, castles and manors served not merely as residences but as potent symbols of authority, centers of administration, and strategic military strongholds. These imposing structures, with their thick walls, moats, and strategically advantageous locations, prioritized defense and control, reflecting the turbulent political landscape of the era. The interior design, while rudimentary by modern standards, reinforced social distinctions, with the lord’s hall serving as a focal point for gatherings and displays of power. From a sociological perspective, these fortifications underscored the nobility’s privileged position and their role in maintaining social order. Peasant dwellings, in stark contrast, offered a glimpse into a vastly different experience of \”home.\” Constructed from readily available local materials like timber and thatch, these humble, often single-room structures served as the center of family life, inextricably linked to the rhythms of agricultural labor. The interior design was functional and minimalist, dictated by the practicalities of daily life. For the peasant class, \”home\” represented not only a physical shelter but also the locus of economic activity and social interaction within the village community. Religious spaces, such as monasteries and churches, also played a vital role in shaping the medieval understanding of \”home.\” These institutions provided not only spiritual guidance but also a sense of community and belonging, offering sanctuary and support in times of uncertainty. The architecture of these sacred spaces, with their soaring arches and intricate stained glass, aimed to inspire awe and reverence, reinforcing the Church’s influence on medieval life. The concept of privacy, so central to modern notions of \”home,\” was largely absent in the medieval period. Family life unfolded in shared spaces, with limited differentiation between areas for work, rest, and socializing. This communal living arrangement fostered strong family bonds and a sense of interdependence, reflecting the social fabric of the time. The interior design of peasant homes, for instance, often included designated areas for specific tasks, such as weaving or food preparation, but these activities were integrated into the shared living space. From a cultural studies perspective, this emphasis on communal living reflects a worldview in which individual needs were often subordinated to the needs of the family and the larger community. The allocation of space within the medieval home, from the lord’s chambers in the castle to the shared hearth in a peasant cottage, mirrored the social hierarchy and the prevailing cultural values of the era. This hierarchical organization extended even to the layout of villages and towns, with the church or castle often occupying a central position, symbolizing the importance of religious and secular authority in shaping the medieval experience of \”home.\”

Early Modern Homes: Privacy and Comfort

The Renaissance, Reformation, and Scientific Revolution collectively instigated a profound transformation in the conceptualization of home, moving away from the medieval emphasis on fortification and communal living towards a more individualized and comfortable domestic environment. The burgeoning humanist philosophy championed personal expression and individual experience, which directly translated into a desire for greater privacy within the home. This era saw a departure from the large, multi-functional halls of medieval structures, giving way to more specialized rooms designed for specific purposes, such as dining rooms, studies, and bedrooms. The increased use of windows, often larger and more numerous than in previous eras, became a hallmark of early modern homes, reflecting both an aesthetic preference for natural light and a symbolic shift towards openness and enlightenment. This new approach to home design was not merely about aesthetics; it also reflected the evolving social structures and cultural values of the time. The architecture of this period began to reflect a growing emphasis on domesticity and the nuclear family, with homes designed to accommodate the needs and activities of individual family units. The rise of the merchant class further impacted housing trends. As trade and commerce flourished, so did the construction of townhouses and urban dwellings, reflecting the growing concentration of wealth and population in cities. These townhouses, often multi-storied and featuring distinct living and working spaces, exemplified the increasing importance of both personal comfort and professional activity within the home. This marked a significant departure from the agrarian-based housing of the medieval period and mirrored the shifting economic and social landscape. Interior design during this period also underwent a significant transformation. Furniture became more refined and varied, reflecting both practical needs and evolving aesthetic tastes. The use of textiles, such as tapestries and curtains, became more widespread, adding layers of comfort and visual interest to interiors. These elements were not just decorative; they played a crucial role in creating more private and intimate spaces within the home. The concept of the home as a reflection of personal identity and status began to take shape, with individuals investing more resources in the appearance and comfort of their living spaces. Cultural studies perspectives highlight how the changing architectural styles and interior design choices of the early modern period were deeply intertwined with broader social and cultural shifts. The Reformation’s emphasis on personal piety and family life, for example, contributed to the growing importance of the home as a private sanctuary and a space for religious observance. The scientific revolution, with its focus on observation and rational thought, also influenced home design, with a greater emphasis on functionality and the efficient use of space. These combined factors led to a gradual but significant shift in how people viewed and interacted with their homes, moving towards a more modern understanding of domesticity and personal space. The changes in architecture and interior design during the early modern period were not just about aesthetics or functionality; they were reflections of deep-seated cultural shifts. The transition from medieval homes to early modern homes represents a crucial turning point in the history of home, laying the groundwork for the further evolution of domestic space in subsequent centuries. The focus on privacy, comfort, and individual expression set the stage for the more elaborate and diverse housing styles that would emerge during the Industrial Revolution and beyond, further solidifying the home as a central element in both personal identity and social structure.

Industrialization and the Domestic Sphere

The 18th and 19th centuries marked a pivotal era in the history of home, witnessing the profound impact of industrialization and urbanization on its very concept. The burgeoning factory system drew masses from rural landscapes to urban centers, leading to the rapid construction of dense, often overcrowded housing. This period saw the rise of tenements and row houses, stark contrasts to the more spacious dwellings of previous eras, and these new forms of housing were often characterized by poor sanitation and limited access to natural light, reflecting the social inequalities of the time. The architecture of these structures, often hastily constructed, prioritized efficiency and cost-effectiveness over comfort or aesthetic appeal, a clear departure from the more deliberate designs of earlier periods. This shift in housing directly impacted family life and community structures, as individuals found themselves living in closer proximity to strangers and often separated from their traditional social networks. The rapid pace of urbanization also led to new social problems, including increased crime rates and disease outbreaks, which further shaped the perception of home as a place of refuge and safety. The concept of domesticity gained prominence during this period, particularly among the emerging middle class. The home became a symbol of respectability and a space where women were expected to cultivate a nurturing and orderly environment. Victorian homes, for example, were meticulously decorated with ornate furnishings and a clear separation of spaces, reflecting the prevailing social norms and gender roles. The parlor became a space for formal entertaining, while the kitchen and servants quarters were relegated to the back of the house, emphasizing a clear hierarchy within the household. This era also saw the rise of interior design as a distinct profession, with magazines and books offering guidance on how to create a fashionable and comfortable home. Colonialism further complicated the concept of home, as European architectural styles were exported to other parts of the world, often disregarding local climate and cultural traditions. This imposition of foreign designs often resulted in housing that was ill-suited to its environment and disrupted indigenous building practices. The impact of colonialism can still be seen in the architecture of many former colonies, serving as a reminder of the complex interplay between power, culture, and the built environment. The mass production of furniture and household goods, enabled by industrialization, also began to transform the interior design of homes, making once-luxury items more accessible to a wider range of people. This period laid the groundwork for many of the modern concepts of home design and lifestyle, as the industrial revolution forever changed the relationship between people, their dwellings, and the surrounding society.

Modernism, Postmodernism, and Globalization

The 20th and 21st centuries mark a period of radical transformation in the concept of home, influenced by the sweeping changes of modernism, postmodernism, and globalization. Modernism, with its emphasis on functionality and efficiency, profoundly impacted architectural and interior design. The Bauhaus movement, for example, championed clean lines, open floor plans, and the use of industrial materials, aiming to create homes that were both practical and aesthetically pleasing. This era saw a departure from the ornate styles of the past, embracing a minimalist approach that prioritized form following function. This architectural shift was not merely aesthetic; it reflected broader societal changes towards industrialization and mass production, impacting the very way people lived and interacted within their domestic spaces. The rise of suburbanization also became a defining feature of this era. Families, seeking respite from crowded urban centers, moved to newly developed suburban areas, often characterized by single-family homes, lawns, and a sense of community distinct from that of city life. This shift had a significant sociological impact, altering family structures and social interactions, as people began to define their identities not just by their work but also by their domestic environment. Postmodernism emerged as a reaction against the perceived rigidity and uniformity of modernism, embracing eclecticism, historical references, and personalized expression in home design. This era saw a move away from the strict dictates of functionalism, allowing for more individual freedom and creative experimentation in architecture and interior design. Homes became a canvas for personal identity, with diverse styles and influences reflecting the unique tastes and preferences of their inhabitants. This shift was not just about aesthetics; it also reflected a broader cultural move towards individualism and the celebration of diversity. Globalization has further reshaped the concept of home, leading to a cross-pollination of architectural styles and cultural influences. Homes now often incorporate elements from various traditions, reflecting the increasingly interconnected world we live in. This has resulted in a rich tapestry of home designs, showcasing a fusion of global styles and local adaptations. The rise of international travel and migration has meant that homes are no longer just reflections of a single culture but often a hybrid of multiple influences, reflecting the diverse backgrounds and experiences of their inhabitants. This has also impacted interior design, with global textiles, furniture, and art becoming increasingly popular. The history of home in this period is thus a complex story of evolving tastes, social change, and cultural exchange. The rise of technology has also played a crucial role, with homes becoming increasingly integrated with smart devices and digital systems. This has not only impacted the functionality of homes but also the way people interact with their living spaces, blurring the lines between work and home life. The concept of home has become more fluid and adaptable, reflecting the changing needs and lifestyles of the modern era. Additionally, social changes related to family structures and personal preferences have led to a demand for more flexible and customizable home designs. This era has seen a move away from traditional family-centric home designs to accommodate diverse living arrangements, including single-person households, co-housing communities, and multi-generational families. The modern home is thus a reflection of the complex interplay between individual needs, social trends, and global influences, showcasing the dynamic and ever-evolving nature of the concept of home.

Suburbanization and the Changing Family

The mid-20th century witnessed a profound shift in the concept of home with the rise of suburbanization, a phenomenon deeply rooted in the history of home and influenced by architectural trends, sociological shifts, and evolving interior design preferences. The single-family home, complete with a yard, became the aspirational symbol of the American Dream and similar ideals across many developed nations. This era saw a departure from the dense urban living of the industrial age, with a move towards more spacious, individualized housing. The architecture of this period often featured ranch-style homes and split-levels, designed to accommodate the growing family and the new culture of suburban life. This architectural shift was not merely about aesthetics; it was a reflection of changing social values and aspirations. Mass-produced furniture and appliances played a key role in this transformation. Factories churned out affordable goods, making home ownership more accessible to a wider range of people. However, this accessibility also contributed to a sense of homogeneity in domestic spaces, with similar furniture styles and layouts becoming commonplace. This period is also significant in cultural studies for how it shaped ideas of domesticity and family life, as the suburban home became the stage for a new era of consumerism and nuclear family ideals. The changing family structure, characterized by an increase in single-person households and diverse family arrangements, also began to challenge the traditional notion of the suburban home. These demographic shifts created a demand for new types of housing and interior designs that could accommodate different lifestyles and needs. The traditional suburban model, designed for a nuclear family, started to appear less relevant to many. This period also saw the rise of car-dependent communities, which further reinforced the separation between home, work, and community. This had a significant impact on social interactions and community engagement, with many suburban residents finding themselves increasingly isolated. The interior design of the era emphasized comfort and convenience, with a focus on practical layouts and easy-to-maintain materials. This focus on practicality was a response to the busy lives of suburban families, where both parents were often working and time was a precious commodity. The social changes of this era also had a significant impact on home design. The rise of feminism, for example, led to a greater emphasis on shared domestic responsibilities and a move away from the traditional gendered division of labor in the home. This had an impact on how homes were designed, with more open-plan layouts and flexible spaces that could be used for a variety of activities. The history of home during this period is not just a story of bricks and mortar, but a complex interplay of social, economic, and cultural forces that shaped the way we live today. The suburban home, with its emphasis on individual ownership and family privacy, remains a powerful symbol of the 20th century and continues to influence housing trends in the 21st century. The impact of these architectural and social changes continues to resonate in the way we design and inhabit our homes today, with the need for flexible, adaptable spaces becoming increasingly important in a world of diverse family structures and rapidly changing lifestyles.

Technology and the Digital Home

Technology’s impact on the concept of home in the digital age is multifaceted, extending beyond mere convenience to reshape how we interact with our domestic spaces. The rise of smart homes, equipped with integrated technology for lighting, security, and entertainment, signifies a shift towards automated and personalized environments. This integration of technology within the architecture of the home reflects a historical trend, echoing the introduction of electricity and plumbing in earlier eras. From a historical perspective, this mirrors previous domestic revolutions, like the introduction of electricity and running water, fundamentally altering daily routines and expectations of comfort. The ability to control various aspects of the home environment through smartphones and other devices has created new possibilities for customization and efficiency, impacting interior design choices and lifestyle preferences. Sociologically, this shift raises questions about accessibility and the digital divide, as the benefits of smart home technology may not be equally distributed across socioeconomic groups. For example, the integration of voice-activated assistants and smart appliances may offer greater convenience for some, while potentially excluding others due to cost or lack of digital literacy. The rise of remote work has further blurred the lines between work and home life, leading to the need for flexible and adaptable spaces. This shift has necessitated a reimagining of interior design, with homes increasingly incorporating dedicated workspaces and multi-functional furniture to accommodate the demands of both professional and personal life. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend, highlighting the need for homes to serve as both sanctuaries and productive work environments. This has architectural implications, with a growing demand for flexible floor plans and spaces that can be easily adapted to serve multiple purposes. From a cultural studies perspective, the blending of work and home life raises questions about work-life balance and the potential for increased stress and burnout. Social media’s influence on our perception of home is undeniable, with curated images and videos showcasing idealized domestic environments. These online representations of home, often meticulously styled and filtered, create a new layer of social comparison and can influence interior design trends. The pursuit of the perfect Instagrammable home can drive consumer behavior, impacting furniture choices, color palettes, and even architectural styles. However, this constant exposure to idealized versions of domesticity can also create unrealistic expectations and contribute to feelings of inadequacy or anxiety. Historically, idealized depictions of home life have existed in various forms, from paintings and literature to television and magazines. Social media amplifies this phenomenon, creating a constant stream of aspirational content that can shape our desires and perceptions of what constitutes a desirable home environment. The concept of home as a sanctuary and a place of personal expression remains central, but it is increasingly intertwined with technology, social media, and evolving work patterns. This interplay of factors presents both opportunities and challenges for individuals and families as they navigate the complexities of creating a home that meets their practical, emotional, and aesthetic needs in the digital age. The future of home design will likely involve further integration of technology, with an emphasis on sustainability and adaptability to meet the changing needs of individuals and families in a rapidly evolving world. This evolution will continue to be shaped by social and cultural trends, as well as advancements in architecture and interior design that prioritize both functionality and well-being within the domestic sphere.

Sustainable and Alternative Homes

The evolving understanding of “home” is increasingly intertwined with environmental consciousness and the pursuit of sustainable living. This shift reflects a growing awareness of the ecological footprint of traditional housing and a desire for more harmonious ways of dwelling. Minimalist living, once a niche lifestyle choice, is gaining mainstream traction as individuals seek to declutter their physical spaces and simplify their lives. This trend aligns with a broader cultural shift towards experiences over material possessions, impacting interior design choices that favor functionality and clean aesthetics. From a sociological perspective, this represents a move away from consumerism and towards a more intentional way of life. Historically, periods of scarcity or social upheaval have often led to similar reassessments of material needs, echoing the current focus on resource efficiency. Tiny houses, with their compact footprints and emphasis on multi-functional spaces, represent an architectural response to this desire for sustainable and affordable housing. The historical precedents for small, efficient dwellings can be traced back centuries, from medieval cottages to early American homesteads, demonstrating a recurring human need to adapt living spaces to available resources. The rise of co-living spaces, particularly among younger generations, reflects not only economic pragmatism but also a renewed interest in community and shared resources. This resonates with historical patterns of communal living, seen in various forms throughout history, from monastic communities to early agricultural settlements. The cultural implications of co-living are significant, challenging traditional notions of family and domesticity. Sustainable design principles are no longer a niche interest but are becoming integral to mainstream architecture and interior design. The use of eco-friendly materials, such as reclaimed wood and bamboo, reflects a growing awareness of the environmental impact of material choices. Historically, building materials were often sourced locally, a practice that is now being revived in sustainable building practices. Energy-efficient technologies, like solar panels and passive heating systems, are also becoming increasingly common, driven by both environmental concerns and rising energy costs. From a historical perspective, this represents a return to more environmentally integrated building practices, reminiscent of pre-industrial construction techniques that relied on natural ventilation and solar orientation. The shift towards sustainable housing is also influencing interior design trends. Natural light, biophilic design principles, and the incorporation of plants into interior spaces are becoming increasingly popular, reflecting a desire to connect with nature and create healthier living environments. This aligns with cultural studies perspectives on the human-nature relationship and the growing recognition of the psychological benefits of incorporating natural elements into living spaces. The minimalist aesthetic, with its emphasis on clean lines and uncluttered spaces, further complements the focus on sustainable living by reducing the consumption of material goods. This shift in design preferences has implications for the furniture industry, with a growing demand for durable, ethically sourced, and multi-functional pieces. This represents a departure from the mass-produced furniture of the mid-20th century, echoing earlier periods where furniture was often handcrafted and passed down through generations. Sociologically, this represents a move towards more conscious consumption and a rejection of disposable culture. The historical parallels with movements like the Arts and Crafts movement, which emphasized handcrafted quality and traditional techniques, are noteworthy. The growing interest in sustainable and alternative housing models reflects a profound shift in how we conceive of “home.” It represents a move away from the traditional emphasis on material possessions and towards a more holistic understanding of home as a place of well-being, connection, and environmental responsibility. This shift has implications for architecture, interior design, and the broader cultural landscape, shaping the future of how we live and interact with our built environment.

Home as a Psychological and Emotional Space

Home transcends mere physicality; it represents a profoundly emotional and psychological sanctuary, deeply intertwined with our sense of belonging, security, and personal identity. From a historical perspective, the concept of home as a sanctuary emerged gradually, evolving from the medieval need for physical security to the modern emphasis on emotional comfort. Castles, once symbols of power and protection, gradually gave way to homes designed for privacy and personal expression, reflecting societal shifts and changing values. This evolution is mirrored in architectural styles, from the imposing fortifications of the past to the open, light-filled spaces of contemporary homes. Interior design further reflects this transformation, with personalized spaces curated to foster emotional well-being and self-expression. For instance, the rise of minimalist design in modern homes often reflects a desire for tranquility and a focus on essential elements, mirroring a broader cultural shift towards experiences over material possessions. However, the experience of home is not universally consistent. For individuals facing displacement due to global migration or social upheaval, the notion of home becomes complex and often traumatic. The loss of one’s physical home can lead to a profound sense of displacement, impacting personal identity and severing ties to community and cultural heritage. Sociologically, this displacement underscores the critical role of home in establishing social connections and providing a sense of stability. From a cultural studies perspective, the concept of home becomes a lens through which we can examine broader societal structures and power dynamics. Access to safe and affordable housing is often unevenly distributed, reflecting systemic inequalities that impact marginalized communities. The design and functionality of homes also reflect cultural values and norms. For example, the open-plan living spaces common in many modern homes reflect a cultural shift towards informality and shared experiences. This shift is further reinforced by the integration of technology into the domestic sphere. Smart home technologies, while offering convenience and connectivity, also raise questions about privacy and data security, reflecting the ongoing negotiation between technology and our personal lives. Interior design trends often reflect these evolving needs, with flexible and adaptable spaces becoming increasingly popular. The growing emphasis on sustainable living is also reshaping the concept of home, with designs prioritizing energy efficiency and eco-conscious materials. This reflects a broader cultural shift towards environmental awareness and a desire for more sustainable lifestyles. Ultimately, the concept of home remains a dynamic interplay between physical space, emotional resonance, and cultural context, continuously evolving to reflect our changing needs and aspirations.

Conclusion: The Evolving Future of Home

The future of ‘home’ is likely to be shaped by a confluence of ongoing technological advancements, environmental concerns, and evolving social norms, mirroring shifts observed throughout history from medieval homes to modern dwellings. We may see a greater emphasis on flexible and adaptable spaces, with homes that can be easily reconfigured to meet changing needs, much like the evolution from the fixed layouts of Victorian homes to the open-plan designs popular today. This adaptability will be reflected in modular furniture, movable walls, and multi-functional spaces, catering to the fluid lifestyles of individuals and families. The history of home reveals a constant interplay between structure and societal needs, and this trend is set to continue. For instance, the rise of remote work necessitates dedicated home office spaces, while multi-generational living may require flexible layouts that can accommodate both privacy and communal interaction. Architects and interior designers are already exploring innovative solutions, drawing inspiration from historical housing solutions and incorporating sustainable materials and smart technology. The integration of technology will continue to evolve, with homes becoming increasingly intelligent and personalized. Smart home systems will anticipate our needs, adjusting lighting, temperature, and security based on our preferences and daily routines. This personalization extends to interior design, where technology facilitates customized experiences, from interactive art installations to mood-sensitive lighting that responds to the emotional atmosphere of the home. From a sociological perspective, this shift reflects the growing desire for convenience and control over our immediate environment, a trend that echoes the historical progression from basic shelter to homes equipped with modern amenities. The concept of ‘home’ will also be increasingly intertwined with sustainability. Environmental concerns are driving a shift towards eco-friendly building materials, energy-efficient appliances, and water conservation systems. This resonates with the cultural studies perspective on home as a reflection of societal values, where environmental consciousness is becoming a defining characteristic of modern lifestyles. Minimalist living, tiny houses, and co-living spaces, reminiscent of historical communal living arrangements, are gaining popularity as alternatives to traditional housing models. These approaches emphasize resource efficiency, community, and a focus on experiences over material possessions, representing a shift in societal priorities. Ultimately, the concept of ‘home’ will continue to be a reflection of our ever-changing world, adapting to our needs and desires while remaining a fundamental aspect of the human experience. Just as medieval homes prioritized security and early modern homes emphasized privacy, the homes of the future will prioritize adaptability, sustainability, and personalized experiences. This ongoing evolution of ‘home’ provides a fascinating lens through which to study the interplay of history, architecture, sociology, interior design, and cultural studies, revealing how our physical spaces reflect our deepest values and aspirations.